Introduction

Yes!

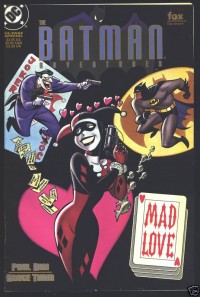

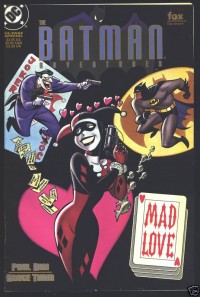

Harley Quinn, a relatively minor figure in the pantheon of DC Comics’ universe, provokes enthusiasm, no, adoration, hugely out of proportion to her apparent importance. I suspect part of this is that though she may not have the oomph factor of some bad girls, she has an enormous, larger than life, vivacity. She clearly enjoys her life immensely (well, most of the time) and that joy communicates itself to the reader. So though Poison Ivy may be your fantasy figure of choice, Harley would have to be the number one candidate for a girl friend to have fun times with.

No!

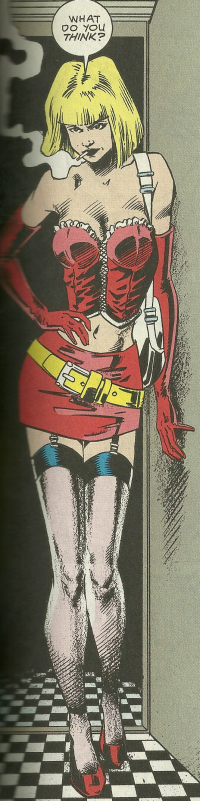

All of which makes it perfectly incomprehensible that DC Comics, in their wisdom, chose to ‘reboot’ her in a deeply regressive way. So instead of a gorgeous, funny, sad, wildly unpredictable and larger than life goddess, she becomes the modern-day cliche of the barely clad babe with attitude, heroine of more bad action movies than one cares to think of. Unsurprisingly, this has somewhat annoyed her fans, but it also begs an interesting question, that is: why would DC Comics think that a generic nearly naked skank was more likely to shift comics than a well-rounded character with an adoring fan-base? So that’s one of my questions.

My next question is related. It would appear that fans have been discontented for a while over the kind of story Harley has been involved in. Though she started out as the Joker’s side-kick, of late she has moved away from him, shifting to a complex will-they, won’t-they relationship with Poison Ivy, which only seemed to resolve itself just before the ‘reboot’. Now, given that Harley’s relationship with the Joker was that of an abused woman, with him humiliating, abusing and occasionally trying to kill her and her escaping briefly only to return, because she was sure he loved her really, why would anyone want to reunite them? Surely her fans should be glad that she has found a stable, loving relationship at last? So that is my second question: given how bad the Joker was for Harley, why would a ‘fan’ want to see her return to him?

She started it

But before answering those questions, I want to look at another. This has been bothering me for some while. It is usually stated that Dr Harleen Quinzel was the Joker’s therapist, that he subverted her therapy to seduce her and then drove her insane, Harley Quinn being the result. This is the ‘orthodox’ view, though it hasn’t gained total acceptance and, indeed, is not followed in Harley’s self-titled series. So we are meant to believe that Harleen Quinzel, the brilliant, near-genius psychiatrist, was blasted away by the Joker’s seduction, and what was left behind was a volatile mad-woman almost as dangerous as the Joker himself. For any number of reasons, I don’t think this is very plausible, so I shall start, in the next section, by attempting to analyse Harley, to see what might really be going on.

About Harley

Some facts

Let’s start the analysis of Harley’s psychopathology by examining some of the facts about her. What one might call the two most obvious can be expressed by saying that she acts like a lovable moron who has a propensity to extreme violence. This is true in as far as it goes; the mistake lies in thinking that because she acts like a moron therefore she is a moron. Because the interesting thing about Harley is that she is a creature of layers. On the surface there is the lovable moron, who is always cheerful, spends her days watching cartoons and has a distinctly childish world-view. Every now and then the mask slips and we see a desperately sad woman underneath. And below her there lurks a woman with a powerful logical mind who surfaces occasionally, makes a few observations and then retreats. So any attempt at understanding Harley has to deal with this almost hidden structure which gives her considerable psychological depth.

Moving on to the second point, Harley does have a distinct propensity for violence, indeed considerably volatility of mood. She more or less specialises in not using the minimal force required to get the job done, but in massive overkill, the goal seemingly being not so much an effective operation as the maximum of theatrical effect. In other words, the violence, which is often comical, and carried out with a knowing, cheeky eye on her audience, is part of the general tendency of all Harley’s actions to be much larger than life. She doesn’t just want to get the job done; she wants to get it done with style and in a way that will not so much impress as give pleasure to those who happen to be watching. So, when she needs to leave her gang to do something private, she doesn’t go through the door: she drops straight down the front of a skyscraper. There is a look of pure pleasure on her face when the Riddler threatens to fight her with a sword. And she always, always delivers the appropriate snappy one-liner before thumping her adversary. She knows the role she’s playing and she loves playing it.

As for Harley’s relationships, her record is not good. Her relationship with the Joker is classically abusive. She loves him, he gives her encouragement, then humiliates her, hurts her and even tries to kill her. She leaves, but can’t stay away, returning convinced that he’s reformed this time, and so on. And so we get into the cycle that can only end in intervention or disaster. What does not help is that, on the whole, her friends tend to perpetuate the abusive pattern. Poison Ivy and Catwoman both treat her as if she is a moron, and so incapable of making decisions or saying anything remotely helpful, often resulting in their own discomfiture because they wouldn’t listen to her. And so, once again, we get a cycle of negative reinforcement: treating Harley as if she is a small child leads to her withdrawing further into childish, dependent behaviour, which reinforces their impression that she is a child, and so on and so forth. It is not a happy state to be in.

Some thoughts

Let’s start with the standard view. This can be basically summed up as being that Harley actually is (and not merely seems to be) a lovable moron who is a psychopath, is utterly dependent on the Joker and behaves like a child because that is what she is. So, as I said above, Harleen Quinzel and any adult aspects of her personality have been entirely erased, leaving nothing behind but an emotionally dependent lunatic. This does not stand up to careful thought. If Harley is actually little more than a psychopathic child, what are the deeper layers of personality that peep out from time to time? Given that the deepest layer is clearly extremely intelligent and has formidable psychological acumen, I would suggest that far from having been erased, Harleen Quinzel is still there, hidden under layers of childishness and dependency, and is perfectly capable of being her old self when she wants to. So the obvious question is, then, why did she choose to retreat from the world?

All the emotional support she needs

I am going to argue that in fact, far from having retreated, Harleen is quietly orchestrating much of Harley’s behaviour from behind the scenes. It is just that the way she chooses to arrange things creates the impression that she has been replaced by a childish, needy psychotic. The real change in her is that she has chosen not to engage with the world on its terms any more, but only on her own. Remember that Harleen Quinzel was of exceptional intelligence, and she was also a first rate gymnast (something Harley clearly has inherited from her). Now exceptional intelligence and ability are all very well, but they have a well-known and very debilitating negative aspect: that is to say, if nothing you do is particularly challenging then it’s easy to get bored and frustrated and drift into depression, destructiveness or worse. Especially if, as we know is the case with Harleen, you have little in the way of emotional support from friends and family.

Now, to a mind that was already in the process of this retreat from reality having discovered that no matter how hard she looked, she couldn’t find worthy peers or anything that was remotely challenging, the Joker would have been a wonderful discovery. His psychoses would be a challenge worthy of her, and sufficient to spur her interest in him. So, I think it’s fair to say not so much that he seduced her away from the straight and narrow as that she was only too willing to leave it, and he merely showed her the way. Especially as it would be very natural for her to question whether, as the world of the legitimate psychiatrist left her parched and dying, it might not be worth seeing if she could finally find what she wanted by turning to crime. So Harleen did not lose her mind and in the process become Harley; rather Harley is a persona deliberately adopted by Harleen for her new role as mistress of crime.

The ticket to her dreams

Of course, it didn’t turn out as she expected; the Joker was even more psychotic than she had thought and so she ended up not as a partner in crime but as a despised hanger-on. Admittedly, even in that role she does her best, being supremely effective at what she does. Indeed, the very larger than life quality that characterises Harley’s every action can be seen as just another example of the over-achiever’s curse: she can’t just do the job, she has do do it in a way that’s deliberately difficult and extremely showy, just to prove to herself how good she really is. This also explains her often rather bizarre choice of target for her crimes: often it obeys a very strict inner logic, known only to Harleen, but it makes no sense in terms of the world that Harley inhabits. She doesn’t see that as a problem, as this is all about seeking stimulation and reward, but her colleagues in crime see it as further evidence that she is nuts. Which helps ensure that she remains at best a minor player. It turns out that the only thing she has that can guarantee a challenge is her relationship with the Joker, so she depends on him for stimulation and easily falls into the cycle of abuse. She does not love the Joker at all; she is dependent on him, or has grown to believe she is, and therefore behaves in like a needy woman in love, but there is no genuine feeling for him. Their relationship is one of mutual exploitation.

Her knight in greenish armour

Things don’t get much better when she does manage to tear herself away from the Joker. Her relationship with Poison Ivy could be her saviour. Unfortunately, though it is fairly clear that Ivy does love Harley, she is too far set in her own conceit of hating all humans to actually be able to admit it until almost the last possible moment. Also, she seems to take the rather ditzy exterior at face value and doesn’t realise that it’s the consequence of an extremely intelligent woman finding herself caught, like a rat in a trap, with no way out save irresponsibility. Thus Harley is treated as a hanger-on. Is it not a surprise that she sinks further into childishness, as her mind begins to close itself off from the world, or that she makes one last, desperate attempt to rekindle her connection with the Joker, the one source of stimulation she thought she knew.

Unfortunately, we will now never know what happens next with Harley and Ivy, whether they do sort things out and develop a proper loving relationship, and Harley begins to get the emotional support required to emerge from her inner exile, or whether things just carry on as before. The outlook, it has to be said, is not good.

About Harley’s fans

Why would anyone want her to go back to the Joker?

Wile E Coyote speaks out

As I said in the introduction, prior to DC’s big ‘reboot’ many of Harley’s fans were agitating for her to return to the Joker, apparently viewing her striking out on her own followed by her partnership with Poison Ivy as being something of an aberration. I find this mysterious. Or rather, I can understand this attitude only if one views Harley purely as an intellectual construct, a piece of fictive property, to be put through hoops for one’s amusement. In this case, it doesn’t matter that Harley is apparently hurt and humiliated, because she isn’t real, and she exists only to amuse by her pratfalls in pursuit of her puddin’. Like Wile E Coyote , she will always spring back into shape.

Fail!

There is an interesting story written by an Italian Communist leader who was invited to attend one of Stalin’s private cinema screenings. He commented that Stalin got very involved in the film and talked to the characters as if they were real people. He then made the sniffy comment that this proved that Stalin was of lesser intellect, because only a clod would actually treat fictional characters as though they were real. This view became very modish in modern fiction and literary criticism, the fad being to discuss the author’s writerly constructs rather than what it was they had written about. And yet, as the plethora of ironic, writerly and completely unreadable novels of this school shows, a purely artificial work of fiction does not live for its reader. Criticism also became obsessed with form as opposed to content, as witness Umberto Eco’s famous essay on Superman, in which he appears to argue that Superman is defective as mythic archetype because the stories unfold in the present tense. Admittedly, it is hard to see how a picture-based medium could do anything but unfold in the present, but apparently that observation is too simplistic, and so Eco builds a massive edifice on this entirely meta-textual observation. He then goes on to bolster his credibility by asserting that there is no need for him to discuss any other comic-book characters, because they are all the same.

Contrary to these ‘intellectuals’, Stalin’s empathy with the movie’s characters was the proper form of reaction to fiction. If, say, Harley were a purely intellectual construct, intended, like Wile E Coyote, to amuse, but no more, what is there that makes her any more memorable than any other such construct? Moreover, can she be said to have any individuality at all? Surely the constructs named ‘Harley Quinn’ in different stories are independent because they exist in independent narratives, and so the concept of ‘Harley Quinn’ becomes meaningless. Thus fiction would be reduced to pure formal games, with no actual meaning. To deny, as do Eco and his ilk, meaning in fiction, in the face of authors’ indignant rejection of that denial, is the height of arrogance and evidence of academics forgetting that their job is to study and not dictate. Now, Harley Quinn exists as an identifiable character, not just in her appearance, but in her personality and behaviour. Though different writers inevitably give a different slant on her, there is an identifiable commonalty that can only exist if there is actually some meaning, some concept of ‘Harley Quinn’ distinct from the marks on paper. And that is why I can discuss her psychology, and so many people can love her and want to emulate her. To view her as purely a fictional thing to make one laugh is a possible interpretation, but it is fundamentally misguided and contrary to the very nature of fiction itself.

Not good

However, if one views Harley as a person (albeit a fictional one) it is hard to see how one can think it better that she return to a highly abusive relationship with someone who is very likely to kill her in preference to a relationship with someone who actually appears to love her. With the exception of one rather gruesome possibility. To a certain mindset, Harley’s ‘mad love’ for the Joker might be seen as being terribly romantic in a way that her more sane feelings for Ivy are not. That is to say, simply by virtue of being unreciprocated and hopeless, it acquires a patina of desperate wish-fulfilment common in bad literature from Jane Eyre to Twilight. In other words, fans who themselves have thwarted romantic longings (and who does not in the full flush of youth?) want her to suffer with them, on their behalf, so they have, as it were, a role-model or proxy. Harley happy with Ivy is of no use to them, as though she may be what they aspire to be, they cannot see any way of actually achieving that state, and her having achieved it is, in fact, a threat (even regardless of the fact that US culture is still regrettably homophobic, and so a loving relationship between two women is likely to be seen as transgressive), because Harley with Ivy is telling them that they could be like her, and not full of thwarted desire, and hence creates feelings of inadequacy. Much better, therefore, to stick with unrealistic romanticism and demand that Harley do likewise.

Why the new look?

WTF?

It is understandable that when one is updating all one’s product lines one wants to make changes. What is not understandable is why, when one has a product, like Harley, that is incredibly successful as it is, one would decide to change it almost beyond recognition. And yet that is precisely what DC Comics have done with the new Harley Quinn, featured in Suicide Squad. So is this an outbreak of corporate insanity, along the lines of ‘new Coke’ (remember that?), or is there actually any form of logic to this change?

There are any number of things that have been lost in this change: the beauty, the charm, the humour, the quality of being lovable. What has been gained seems to boil down to two things, both regrettable, but both terribly popular right now: she looks ‘edgy’, and she is wearing considerably fewer clothes than she used to. Now, ‘edgy’ is one of those qualities that are terribly popular, apparently extremely desirable, and yet strangely hard to define. It seems almost to fill the same space that ‘grunge’ did about a decade ago, as the ultimate in socially approved counter-culture (think about it). In as far as it means anything, it seems to involve deliberately not doing a proper job of whatever you’re at and then claiming that the defects make your work somehow more authentic. So the fact that New Harley’s costume is grotesquely ill-suited to a fighting woman is not important and to think about such things is to miss the point: what matters is the look. In other words, what we have here is the old-fashioned cult of amateurism beloved of bad artists the world over. There are quite enough bad comics as it is; why do DC feel the need to give us more?

What hath they wrought?

The second point is even less forgivable. We supposedly live in a post-feminist age. Apparently, or so we are told, all the battles for equality have been won, and there is no need for feminism any more. Women can be comfortable with femininity again. And yet women in movies are relegated to being scantily clad onlookers or neoprene clad babes, one major studio has announced that its policy is to make no movie with a female principal character, and Power Girl has been downgraded from one of the mightiest of superheroes to a trophy girlfriend. And as a part of DC’s ‘reboot’ Harley, whose costume was eminently practical for an athletic criminal, and exposed precisely nothing (while leaving no doubt as to just how shapely she was) has been replaced by New Harley, who simultaneously is less attractive, but shows off a lot more. And this, remember, is part of a move on DC’s part to try to attract younger readers. In other words, they believe that younger readers prefer their women objectified. Which may be true, but succumbing to such a demand is a dreadful state of affairs for a company like DC with a proud history of campaigning for liberal political issues.

Envoi

I had hoped to end this piece with an interview with its subject. Unfortunately, Dr Quinzel’s busy schedule made it impossible for us to catch more than a few moments to speak to one another. She did, however, recommend this extract from the diaries of Dr Arkham, which she said she hoped would be amusing and instructive. Attempts to contact Dr Quinzel’s partner, Dr Pamela Isley, failed. However, I did receive an unmarked package containing a plant which, when watered, proceeded to eat my dog, the postman and seventeen pigeons, and staunchly repelled my attempts to expel it from the house. I took this as a gentle hint and ceased my efforts.